Art in Japan has been through all the same upheavals as art in the west, but no other country has managed to retain so much of its own distinctive character. The defining characteristics include a respect for tradition that shines through even in a critical or satirical mode; a love of beauty and craftsmanship; and a reluctance to draw boundaries between art and craft. All these features are on prominent display in Kamisaka Sekka: Dawn of Modern Japanese Design at the Art Gallery of NSW. It is, without doubt, the most sheerly beautiful exhibition we have seen in Sydney this year. The nucleus of the show is the work of Kamisaka Sekka (1866-1942), an acclaimed artist and designer who fell into obscurity for sixty years following his death, but whose reputation has been restored over the past decade.

Curator, Khanh Trinh, explains Sekka’s neglect by the fact that he “dared to be un-modern in age of tremendous change.” One could argue that today we are living through a time of even greater change, although we are not ‘modern’ in the twentieth century manner. For much of that period pundits nurtured the illusion that art was progressing towards some intangible goal, while anything that looked to the past was seen as nostalgic or reactionary. Having come through the fog of modernism we are more willing to accept that certain aspects of art have a timeless quality. This is true even of those forms that seem the most superficially stylised. The same forms are rediscovered and reworked by artists widely separated in time. Sekka is a textbook example, having come to fame with a version of the style we call Rinpa – which takes its name from the last syllable of the name of the artist, Ogata Korin (1658-1716), who was one of the masters of this school in the 17th century.

Ogata Korin and his brother, Ogata Kenzan, will always be associated with Rinpa, but they were not its originators. The two artists who pioneered the style were Hon’ami Koetsu (1588-1637) and Tawaraya Sotatsu (c. 1600-40), who proceeded the Ogatas by half a century. Koetsu and Sotatsu were also traditionalists, taking their lead from the art of the Heian period (794 -1185 CE).

The first part of this exhibition features work by Hon’ami, Sotatsu and the Ogatas. The second is devoted to the diverse creations of Sekka, and the third brings us up to the present day, with Rinpa-inspired paintings and fashion.

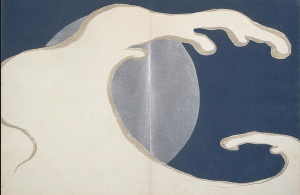

It is difficult to define Rinpa, which is more of a sensibility than a movement. Artists worked across many different media: brush-and-ink paintings, calligraphy, woodblock prints, decorated screens, fans, lacquerware, ceramics, and textiles. They depicted plants, grasses, fish, birds, animals, landscapes, and scenes from the literary classics. Some pieces were remarkably simple, such as the delicate ink works by Ogata Korin or Nakamura Hochu, while others were intended to dazzle. The most striking examples are probably Sekka’s two large folding screens covered in gold leaf, one featuring brightly coloured fans, the other, blue and white irises.

Even though he was an avowed traditionalist, Sekka’s work was subject to many different influences. He had travelled to Europe, where he studied the Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau and Jugendstil. Like many Japanese artists and scholars, he recognised that these European avant-gardes owed a huge debt to Rinpa. Yet Japanese taste was seduced by western adaptations, and Sekka was astute in creating works that fitted in with this vogue, balancing tradition and contemporaneity.

Three volumes of woodblock prints titled, The world of things (1909-10) combine conventional Japanese imagery and the most dynamic compositions. Details are selectively eliminated in favour of bold, flat expanses of colour. Some pictures feel like snapshots, others like emblems. The series is a masterful synthesis of styles, proving that the past and the present could co-exist in one body of work. Sekka aims at a decorative effect that transcends the facile task of pleasing the eye, and transports the viewer into a world in which everyday scenes take on a magical power.

Looking at these prints, and the range of other works in this show, one is struck by the vitality of Sekka’s imagination. We tend to associate craft and design with ideas of repetition and functionality, but he has taken on every medium with the intention of doing something surprisingly original, while using techniques and motifs that have been refined over centuries. The key to his style is his love of colour. Trinh tells us that no ink monochrome works by Sekka are known to exist. Every work is charged with the most ravishing colour, applied with the knowledge that a touch of bright red can make a pale, blank space feel suddenly alive.

The third part of the exhibition, found in the upstairs section of the Asian galleries, is a small, well-chosen selection of works that show how artists have been able to adapt the Rinpa aesthetic to contemporary ends. Ai Yamaguchi draws on typical manga imagery with a group of girls with big eyes, clustered together within “a barrel-shaped house”, resembling a screen that has closed upon itself. The images are simultaneously cute and sinister – a familiar combination for manga or anime.

Taro Yamamoto’s works are equally playful – adding Coke cans, rubber ducks and vacuum cleaners to Rinpa imagery on fans and screens. If you would like to see more of Yamamoto’s witty, beautifully executed pictures, he is having a solo exhibition with Art Atrium in Bondi Junction, until 11 August.

It is good to see Akira Isogawa in this company, as he has drawn extensively on the Rinpa traditions of Kyoto, the city of his birth, to give a new dimension to Australian fashion. I’m no authority on the subject, but if we acknowledge a great fashion designer as an artist, almost from the moment he appeared, Isogawa has seemed a cut above anything else in the local rag trade.

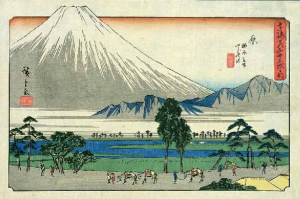

Another side of Japanese art is on display at the Japan Foundation Gallery, where one may see the complete series of Ando Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido. The last time the complete series was shown in Sydney was at the Art Gallery of NSW in 1985, so we are overdue for another look at this most famous series of woodblock prints.

The exhibition was originally intended for the Manly Art Gallery and Museum, but scheduling problems meant that the Japan Foundation had to take over. They may now be pleased about this arrangement, as the show is drawing big attendances.

How could they go wrong? Hiroshige (1787-1859) is one of the immortal names of Japanese printmaking, along with Hokusai and Utamaro. He is more of a landscape artist than these slightly earlier figures, although he took his lead from Hokusai’s example.

The Tokaido was the famous highway that ran along the coast from Edo (now Tokyo) to Kyoto. A journey of approximately 500 kilometres it would usually take 16 days on foot, although a fast courier might do it in three. Today the bullet train does the same trip in 2 hours and 18 minutes.

The Tokaido was also a tourist route, with inns, shops and brothels established at all the major stopping points. Cheap souvenir prints of the journey were sold like postcards.

Now that Ukiyo-e prints are treated as rare and valuable works of art, we tend to forget that these images were produced as mass collectables. Whereas the Rinpa artists made exquisite objects for connoisseurs, Hiroshige’s prints were part of popular culture.

This doesn’t bear too much reflection, as it casts a dismal light on the state of popular culture today. Hiroshige’s cheap, disposable prints – which occasionally made their way to Europe as packing paper in crates – are also works of art of tremendous sophistication. There are subtle borrowings from western art in the use of perspective, and any number of compositional innovations. Hiroshige was particularly skilled in the creation of a pictorial space that alternates between intimate close-up and infinite distance. These works are filled with anecdote and humour, and a profound love of nature.

One curiosity of this show is that many of the prints are accompanied by photographs, showing what each ‘station’ looks like today. Beyond the obvious observations about how these areas have changed, the photos allow us to see how much Hiroshige has brought to these pictures. He did not set to simply ‘capture’ a landscape, as a photographer might, he actively reinvented it – making each scene into a stage on which the large and small acts of life are performed.

Kamisaka Sekka: Dawn of Modern Japanese Design, Art Gallery of NSW, June 22 – August 26, 2012

Hiroshige: 53 Stations of the Tokaido, Japan Foundation Gallery, July 13 – August 9, 2012 Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, July 21, 2012