There’s a study to be written on artists who are the son or daughter of an already famous artist. In Australia there are many examples but the best story is that of Hans Heysen and his fourth daughter, Nora. This relationship is explored in Hans and Nora Heysen: Two Generations of Australian Art, at the National Gallery of Victoria. It’s the latest in a succession of recent shows devoted to the Heysens, and also the most illuminating.

Sir Hans Heysen (1877-1968), who spent his entire working life in Hahndorf in the Adelaide Hills, was one of the great names of 20th century Australian art, known for his majestic paintings of gum trees. Nora Heysen (1911 – 2003), who made her home in Sydney, was an accomplished painter of still lifes, genre scenes and portraits. She was the first female war artist and the first woman to win the Archibald Prize, although for long periods she worked in obscurity.

If I had to nominate a signature work for each artist, I’d point to Hans’s iconic landscape, Red gold (1913), and Nora’s breathtaking still life, Eggs (1927). In this juxtaposition the differences are obvious, but life has a habit of blurring the contours.

Hans’s career was one long succession of honours while Nora’s was a fractured, stop-start affair. After being neglected for so many years there was a sudden surge of interest in her oeuvre, with notable exhibitions being held in 1989, 2000 and 2009. Over the same period we’ve seen a touring Hans Heysen retrospective which visited seven venues over 2008-11. Hans also starred in a 2002 exhibition of art from the Flinders Ranges.

The result of these shows has been a popular rethinking of the Heysens’ place in local art history. Nora’s star has risen while her father’s has declined. Hans is viewed as a throwback to another age, Nora as a woman who struggled for recognition in an oppressive, patriarchal society. There’s an element of truth in these ideas but the full picture is much more complicated.

Curator, Angela Hesson, has put together a thoughtful survey that teases out the subtleties in the father-daughter relationship, showing that Hans and Nora had much more in common than any Hollywood scriptwriter would allow.

Nora was no youthful rebel and Hans never the stern patriarch. It was a close, loving family connection in which Nora struggled to find her own artistic identity and escape from her father’s giant shadow. Hans for his part did everything he could to assist his talented daughter, but his efforts often did more harm than good.

As late as 1962 we find Nora telling an interviewer: “I don’t know if I exist in my own right”. She was over 50 and still feeling she was nothing more than the great man’s offspring. This was the theme of much of the commentary after her Archibald Prize victory in 1938, with some competitors decrying favouritism because her father had friends among the trustees.

One crucial period for Nora came in 1934-37 when she had moved to London following a highly successful exhibition in Adelaide. Like Australian artists of preceding generations she saw London as a finishing school where she would pick up the vital skills she needed to become a successful artist. Instead she found herself devastated by scathing critiques from figures such as Bernard Meninsky and Sir Charles Holmes. She was not modern enough for the former or traditional enough for the latter, but both were merciless.

Hans had arranged for Nora to meet with Holmes whom he considered a personal friend, but the contact proved both patronising and destructive. Nora’s melancholy self-portrait, Down and out in London (1937) records how she felt about the experience.

When we look at the sheer level of skill in Nora’s work it’s clear she lacked nothing in comparison with so many better-known artists. A still life of quinces from 1934 is painted with the precision of an old master, while Corn cobs (1938), with its broken brushwork and shimmering light shows she had absorbed modernism’s lessons more thoroughly than she might have claimed.

One could not, however, make a textbook modernist out of Nora. Her artistic idol was Vermeer, whose influence echoes throughout her work in paintings such as Cedars interior (c.1930), which features a reproduction of the Girl with the Pearl Earring; and London Breakfast (1935), an updated version of a Dutch interior.

In this show we also see a more adventurous side of Hans during his youthful sojourn in Europe from 1899-1903. Although devoted to the Barbizon school he was also open to the influences of Symbolism and Art Nouveau. His masterpiece in that regard is Mystic Morn (1904) which he painted on his return to Australia. It won the Wynne Prize that year, and has remained one of the most popular paintings in the collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia.

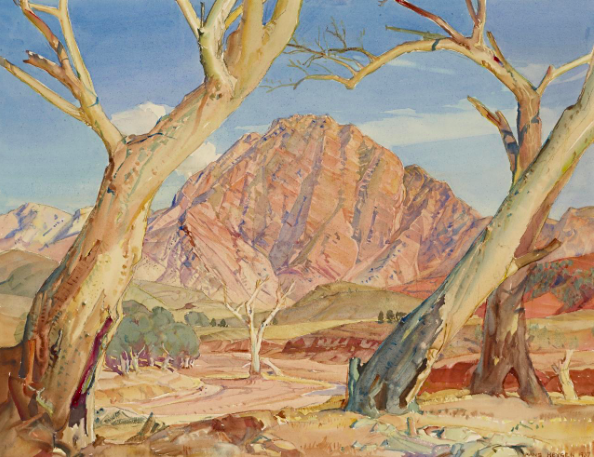

After the death of his daughter, Lilian, from meningitis in 1925, Hans was so distraught he couldn’t find solace in his usual haunts. Instead he paid the first of ten visits to the Flinders Ranges where he would paint “the bare bones” of the landscape. In watercolours such as Guardian of the Brachina Gorge (1937) he experimented with a strikingly flat, bare style. Conscious of where this was heading he wrote to Sydney Ure Smith: “here is the very thing you moderns are trying to paint.”

After the death of his daughter, Lilian, from meningitis in 1925, Hans was so distraught he couldn’t find solace in his usual haunts. Instead he paid the first of ten visits to the Flinders Ranges where he would paint “the bare bones” of the landscape. In watercolours such as Guardian of the Brachina Gorge (1937) he experimented with a strikingly flat, bare style. Conscious of where this was heading he wrote to Sydney Ure Smith: “here is the very thing you moderns are trying to paint.”

It’s a mark of his innate conservatism that Hans would see Ure Smith as a leading avatar of the “modern”, yet some of the Flinders Range pictures are as radical as anything painted in Australia at that time.

The Hans Heysen one sees in this show is a devotee of art and nature. He was not the least bit religious, he didn’t consider himself a representative of any particular school. Above all, he did not see his work in the same nationalistic terms that his friend and supporter, Lionel Lindsay espoused. Lindsay was an aesthete but also an ideologue, happy to champion artists such as Heysen and Arthur Streeton for their pastoral vision of Australia while denouncing modern art as a hoax perpetrated by Jewish art dealers. His small book, Addled Art (1942) is a nasty piece of Anti-Semitism that would look pretty sick at the conclusion of World War Two.

Hans was a pacifist and a humanist. Having been born in Germany he found out what it was like to be treated as a pariah in one’s adopted country during the First World War. In his approach to art, and all his dealings with Nora, he comes across as a thoroughly decent character, albeit a terrible stodge. He was no different when he was in his early twenties, living in a tiny room in Paris. La vie Boheme held no attraction for Hans – it was early to bed, early to rise, and hard work in between.

If he made life tricky for his beloved daughter it wasn’t because of he was a harsh, jealous parent. On the contrary, as a model of rectitude in both life and art he was an impossible act to follow. It’s so much easier when our role models have a few reassuring flaws.

Hans and Norah Heysen: Two Generations of Australian Art

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 8 March – 28 July, 2019

Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, 30 March, 2019