Most children draw instinctively as a way of understanding and taking control of the world. If the great majority of us stop drawing at a certain age it’s not because we have attained a level of mastery. On the contrary, at around 9 or 10, so psychologists tell us, we become self-critical, feeling we don’t draw well enough.

Artists were those children who remained pleased with their efforts and continued to get pleasure from drawing. It’s easy to spot an aspiring artist: they’re the ones who draw in the margins of their school books. They’re the ones who ignore St. Paul’s advice that adults should put away childish things. We should all be thankful of their efforts because a world with no time for the playful activity of drawing would be a desolate place.

On the other hand the all-encompassing satisfaction an artist can take from their own work explains why so many are utterly self-absorbed. If we say an artist ‘lives in another world’, that’s an observation rather than a criticism.

In Real Worlds, the latest installment of the Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial, curator, Anne Ryan, brings together the work of eight artists who delve deeply into their own imaginations. She might just as easily have chosen artists who specialise in landscapes, portraits or still lifes; she might have looked at abstract artists for whom drawing is primarily a matter of process, mood or gesture. Instead she has opted for eight, highly individualistic talents that resist categorisation.

It’s an adventurous selection. Two out of eight are women, a division only a female curator could pull off nowadays. Danie Mellor is probably the most high-profile inclusion while Peter Mungkuri is a rising star. Helen Wright and Matt Coyle have well-established reputations; Martin Bell, Nathan Hawkes, Becc Ország and Jack Stahel might be classed as emerging artists.

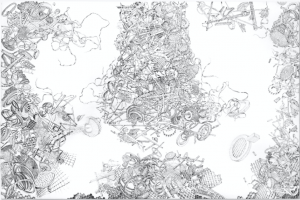

If proof were required that art is a way of extending childhood indefinitely, look no further than Martin Bell’s monumental, Martin Son of the Universe, what me worry 2018-19. On 75 sheets of paper, Bell has crammed in every toy, action figure and superhero, every snippet from Mad magazine that crowded into his pre-pubescent mind during the 1980s. This pen-and-ink extravaganza has overtones of Bosch and Bruegel without the underlying threats of damnation. There is no implicit moralising in Bell’s work, merely an inventory of the countless pieces of pop cultural data the average child might have absorbed from comic books, TV and movies.

It may have seemed like heaven at the time but this avalanche of characters resembles a kind of hell when it is all brought together in a vast, retrospective panorama. How could one even begin to decode the ideological messages, the wholesome or subversive aspects of this plague of images? Bell’s multi-panelled drawing is big enough to wallpaper a room should anyone enjoy the idea of being completely enclosed in their own (or the artist’s) childhood obsessions.

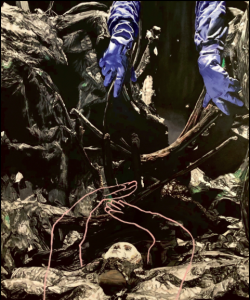

Matt Coyle’s works have a crisp, graphic quality but are as cryptic as stills from an unknown movie. In Dugout a pair of hands in blue gloves hover over a figure that looks as if it has been buried under a pile of wreckage. In The switch, a rough-looking character in a hoodie manhandles a head, against a nocturnal backdrop of façade-like houses and craggy mountains.

Coyle’s illustrative urges make him a natural complement for artists such as Bell and Nathan Hawkes, whose large, brightly coloured pastel drawings have a dream-like quality. Hawkes’s fantasies have no gothic tendencies, as the artist takes such obvious enjoyment in the delicate play of colour his medium allows. One can appreciate the skill and patience that has gone into these pictures because badly-used pastel can degenerate into a smudgy mess.

Hawkes has a taste for vaguely poetic titles such as dreamed summer hour of your childhood – a striking image of a red brick wall with a schematic figure lying slumped on the grass in the foreground. The decoration and ambiguity are reminiscent of artists such as Pierre Bonnard and Odilon Redon. In at least two of these works, bright, diffuse light plays a prominent role but it’s nothing like the harsh glare of an Aussie summer’s day.

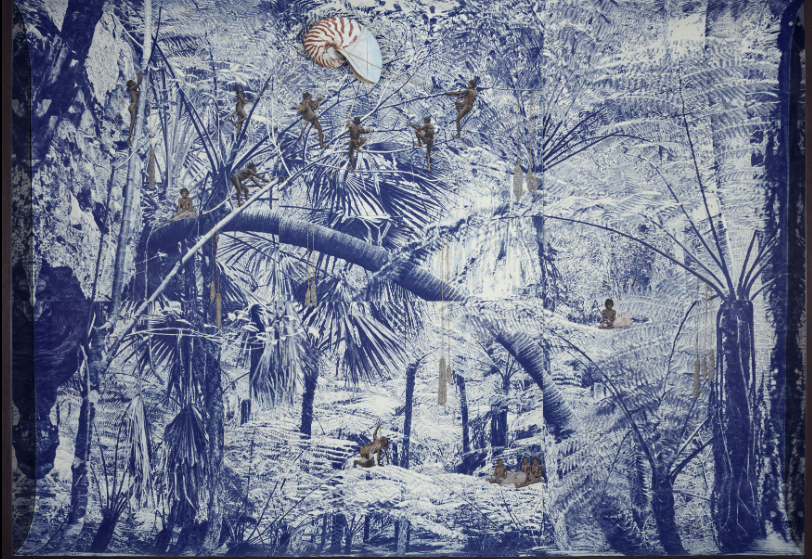

Danie Mellor is the only other artist that employs colour – in his case a distinctive blue, as found on Delftware. It symbolises a mixture of the exotic and domestic, the commodification of an oriental style for a western market. Mellor depicts the lush rainforests of far north Queensland as they might have appeared on a dinner plate, interrupting this ironic idyll with the Lilliputian forms of Aboriginal people clambering through the shrubs and trees.

These images are ways of framing and reimagining the pre-colonial past. Mellor, who is of mixed indigenous and Celtic ancestry, is fascinated by indigenous knowledge, although he can’t disavow his own, cosmopolitan underpinnings. The critical aspect of these images is offset by a powerful nostalgia.

There’s no ambiguity about Peter Mungkuri who hails from Indulkana in the South Australian desert regions. Mungkuri’s black-and-white images of trees are as dynamic as anything dreamed up by the Futurists. They are so full of abstract energy it’s almost impossible to visualise the hot, dry landscape from which they originate. The four panels of Mungkuri’s Punu Ngura (Country with trees) provide a dramatic illustration of the way an indigenous artist views his own country, seeing abundance and fertility where a visitor might see only dry, red earth.

Becc Ország’s fastidiously detailed landscapes give the impression of close observation, but these scenes have been sourced from the Internet and subtly transformed before being set down in pencil on paper. Antique heads pop up like ruins of a lost civilisation, a tiny golden cross glints in the sky, disjointed words and phrases drift across the bottom of the picture. Ország’s technique may be painstaking, but she also practises a form of free association, threading tiny stories and symbols into her non-specific forests.

Helen Wright and Jack Stahel both present personal visions of science and technology. Wright’s two large Scrap stack drawings show a remarkable concern for composition in crafting images of decay and disorder. The artist is lamenting our mania for progress at all costs, the tide of waste and built-in obsolescence upon which our civilisation surfs. And yet, her apocalyptic visions of junk are Baroque in nature, imbued with a perverse form of beauty.

Stahel, the youngest artist in the show, stages an elaborate scientific masquerade, complete with diagrams, three-dimensional fragments of broken machinery and tiny scraps of writing. It’s pure science fiction: part homage, part satire. There’s little concern for aesthetics but an impressive feeling of obsession – as if we’re looking at a hobby pushed to psychotic extremes.

Stahel’s reality may not be yours or mine, but the curator’s theme seems to argue for the existence of multiple ‘real’ worlds. She posits an expanded view of what is real, accepting that each of us inhabits a personal reality that may diverge sharply from our shared, day-to-day version. The positive spin on that idea is to be found in Walt Whitman’s exclamation: “I am large, I contain multitudes”. It works well within the art gallery, but look to America today to see the negative consequences of living in a land of multiple realities.

Dobell Drawing Biennial 2020: Real Worlds

Art Gallery of NSW, 24 October, 2020 – 7 February, 2021

Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, 28 November, 2020