Do we really need another survey of Australian Impressionism? It’s been 14 years since the National Gallery of Victoria’s previous overview of the field and one wonders what new breakthroughs have occurred since then. In 2007 it still seemed a novel idea that we might call this group of artists “Impressionists” in place of more restrictive labels such as “The Heidelberg School”. The previous exhibition set out to establish a canon by including the works of only five protagonists: Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Charles Conder, Fred McCubbin and Jane Sutherland.

It seemed a big stretch to include Sutherland who was self-evidently a lesser talent, although the reason wasn’t hard to discern. It had become all-but-impossible to do a show with no female artists, even when the inclusion of a woman painter went against the premise of the exhibition and appeared to be a flagrant act of tokenism.

Fast-forward to 2021 and the political pressure to include women and indigenous artists in virtually everything is relentless. The NGV could have opted to lie low and forget about the Australian Impressionists for another decade or so, but instead it has gone onto the front foot, inviting art historian, Anna Gray, to act as guest curator for a new, homegrown blockbuster: She-Oak and Sunlight: Australian Impressionism.

Gray’s approach has been almost the opposite of that taken by curator, Terence Lane, in 2007. The same icon pictures such as Roberts’s Shearing the Rams, Streeton’s Fire’s On, Conder’s Holiday at Mentone and McCubbin’s The Pioneer, are on display but the range of artists has been expanded rather than narrowed. There is a predictable new emphasis on female artists and an acknowledgement of the Aboriginal presence that extends to putting the names of indigenous ‘nations’ on the wall labels, although this may have been an afterthought as these names are not included in the catalogue. Eaglemont, for instance, is “Wurundjeri Country”, while Richmond is “Dharug Country”.

As for women artists, not only do we get Jane Sutherland, but also Ethel Carrick, Clara Southern, Jane Price, May Vale, Ina Gregory, Grace Joel, Mary Mayer, May Moore, Helen Peters, Violet Teague, Iso Rae and Florence Fuller. There are even a couple of frame designs by Tom Roberts’s missus, Lillie Williamson, who earned a living for the couple in England while her husband hung around the Chelsea Arts Club feeling depressed and lethargic.

If this sounds like a complete feminisation of Australian Impressionism, guess again. Most of these artists are represented by only one or two works. We certainly don’t see the best of Carrick or Teague, and much of what we see of the others is not especially impressive. Clara Southern has two well-known pictures, The Old Bee Farm (c.1900) and Evensong (c.1900-14). Even on the strength of such slender evidence she looks a better painter than Sutherland, who has four works in the show.

None of this bears comparison to Roberts, with 58 works, Streeton with 45, or Conder with 36. McCubbin has a mere 12 but they are well chosen to show him at his best. The other leading contender for a spot in the A team is John Russell, represented by 10 pieces.

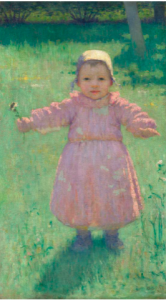

Of all the women artists it’s Iso Rae (1860-1940) who stands out, with two really fresh, Post-Impressionist paintings, the best being Young girl, Étaples (c.1892). But as Rae left Australia at the age of 27 and spent the rest of her life in France and England, she never had to try and carve out a career in her native country. The same applies, to a lesser extent, to the globe-trotting Florence Fuller (1867-1946), who shares a wall – and a progressive outlook – wth Rae.

One of the innovations of this show is the discrete inclusion of works by Europeans such as Monet, Manet, Sisley, Casas and Whistler, which allows us to measure the degree of influence they exerted on their Australian counterparts, and conversely, the orginality of the local product. By and large, the most famous Australian paintings justify their reputation. Roberts’s attempts at modern history painting, from Allegro con brio, Bourke Street west to Shearing the rams, deserve to be viewed as classics; as do Streeton’s great landscapes, notably Fire’s on, Spring, and ‘The purple noon’s transparent might’. Emanuel Phillips Fox is arguably a little under-represented in this show, but Art Students (1895) alone would be enough to secure his place in the pantheon. David Davies’s Moonrise (1894) is a masterpiece for the ages. There’s also a small, unusually vibrant painting called The Swing, by A. Henry Fullwood, subject of a new biography by Gary Werskey.

One of pleasures of this exhibition is the intelligence of the hang. Works have been selected and arranged in a way that creates a productive dialogue between images. The icon pictures have been held back to create a grand finale in the last room, but in almost every gallery there’s something to be learned by looking from one work to the next (and back again). I can also recommend Anna Gray’s catalogue essay, which charts the twists and turns of Australian Impressionism in the most simple, lucid manner.

There are a few new additions that add spice to the story for those like me who know it all too well. Foremost is Robert’s small landscape, She-oak and sunlight(1889), which gives the show its title. A roughly-daubed composition in blue, gold and brown, the work might be seen as a genuine ‘impression’.

The exhibition has tried to address the bunyip in the room – the indigenous issue – by including five works by William Barak (c.1824-1903), a celebrated leader of the Coranderrk Aboriginal community. Barak’s pictures of tribal men dancing in long, possum-skin cloaks, are full of rhythm and verve, but their actual relationship to Australian Impressionism is zero. They are included as a reminder of other traditions and viewpoints that were overlooked at the time.

She-oak and Sunlight is a lesson in how to do a revisionist exhibition that respects the historical record but keeps the worst ideological fantasies at bay. While there may be a remarkable number of women artists in this selection no outlandlsh claims are made about their importance or influence. Likewise we can accept Barak as a symbol of an indigenous world that was being pushed aside as the Impressionists rode the suburban rail lines to diminishing patches of bushland, but it would be foolish to attempt comparisons with Roberts or Streeton.

We may vehemently disapprove of the historical treatment of women and Aboriginal people but history itself couldn’t care less. For curators and critics it’s easy to strike militant poses but difficult to be both truthful and fair. This well-planned exhibition makes strenuous efforts to get the balance right.

She-Oak and Sunlight: Australia Impressionism

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne,

2 April – 22 August, 2021

Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, 1 May, 2021